My Very First UX Design Project

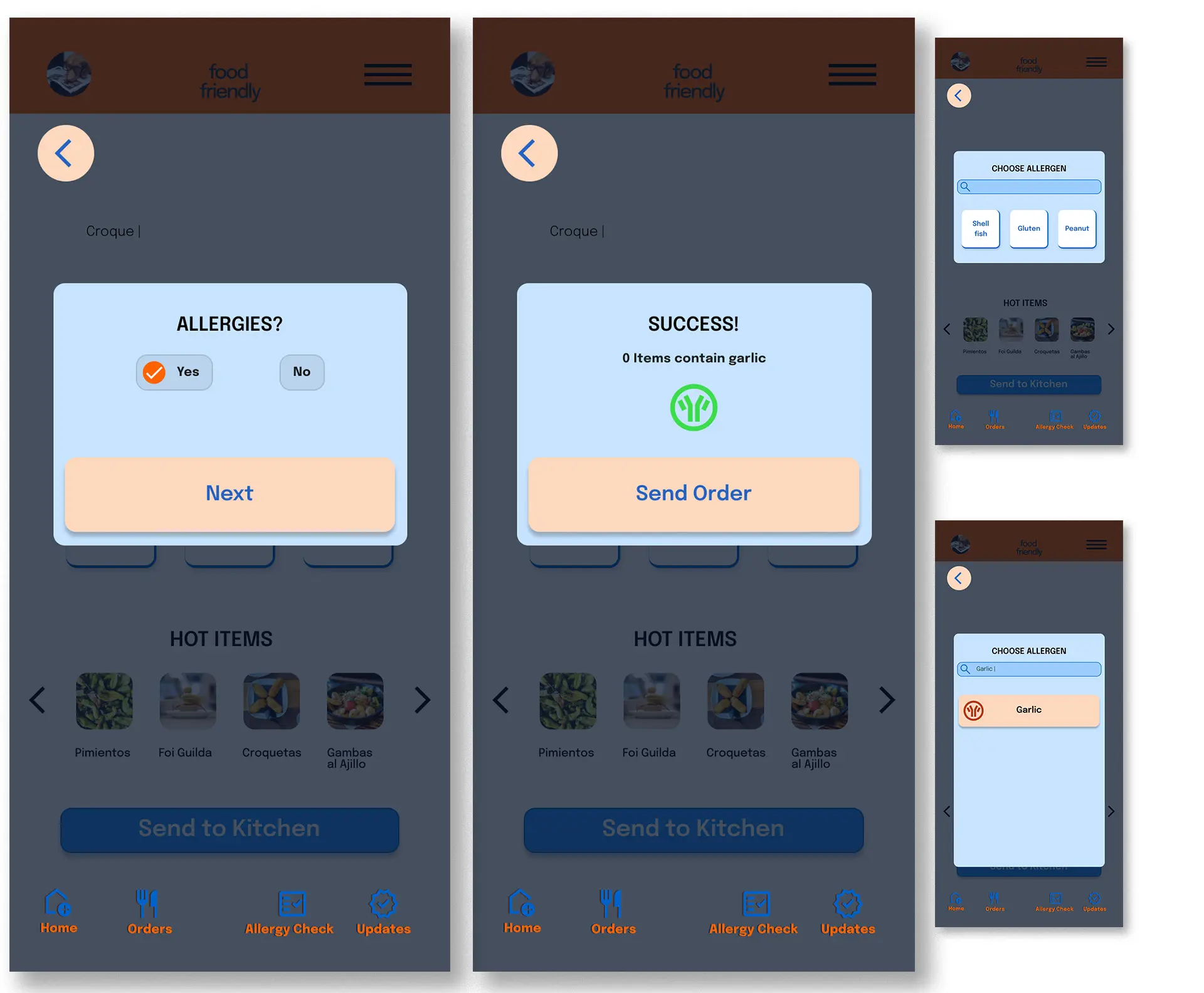

Food Friendly—a restaurant POS system I designed as part of the Google UX Design Certificate. It was ambitious, scrappy, and full of good intentions. My approach was like trying to renovate a house by starting with the doorknobs—technically possible, but backwards and exhausting.

This is the story of how I learned that in design—especially now with AI tools that can generate interfaces in seconds—the hardest part isn’t creating solutions. It’s knowing which problems deserve solving and how to leverage a systems-thinking mindset to truly harness the power of AI in the design process.

The Project: Ambition Meets Inexperience

Oftentimes new designers will use a tool like Sharpen.design to generate a design challenge (known as a prompt) that they can solve as an early portfolio project. This was the case for me when I was working through Google’s UX design certificate, only the instructors gave me a list of prompts to choose from. Here’s one example:

“Design an app and a responsive website for people to find, dispute, and pay their parking tickets.”

Instead of choosing one of the provided prompts I shaped the brief to fit a personal pain point. As someone who had worked in restaurants, I saw an opportunity to redesign the chaotic process of allergy communication, daily specials, and ingredient tracking.

So I tried to design a product that could do… all of that.

Here’s the prompt that I eventually established for myself:

“Design an app that streamlines the communication workflow for front of house restaurant employees and simplifies allergy checks, pre-shift meetings, and food inventory.”

At this point, my marketing instincts were already framing the story of the product, but my design nescience weaved a net of ambiguity that eventually got in the way of delivering a salient case study. I had all the enthusiasm but none of the architecture.

The Cascading Complexity Problem

Every feature I added to Food Friendly created three new problems I hadn’t anticipated—a cascading complexity that nearly killed the project before it began.

“Without understanding this architecture, I’d been trying to grow a tree by gluing leaves together.”

I started trying to solve the allergy checks and quickly realized I needed a way for our users to input ingredients for each dish into the system. This had me framing the target user to back of house employees, allowing them to easily enter ingredients for each individual dish. I started asking questions about what this user flow might look like, and pretty soon I was drowning in something I didn’t yet know how to manage: database architecture, a dev team issue. I also needed to make the allergy checks useful for front of house, customer-facing employees. And how do I make this information presentational so that employees can quickly review daily specials with keywords that optimize salesmanship? What does it look like when a staff member needs to mark an inventory item as “out of stock”? I was so focused on designing the entire forest, I never properly planted a single tree.

I was paralyzed by the act of thinking through the entire product just so I could come up with a usable design prompt. I felt like I was living a cruel math problem: If one feature spawns 3 problems, each problem needs 2 solutions, and each solution creates 2 edge cases, how many design decisions is Matt juggling by level 3?

Answer: 24 design decisions for just one original feature. That’s when I realized I was drowning in complexity without a life raft.

Later, at TechFleet, I learned what I’d been missing: the hierarchy of product thinking. An MVP isn’t a small product—it’s one branch of a larger system. A feature isn’t standalone—it’s a leaf on that branch. Without understanding this architecture, I’d been trying to grow a tree by gluing leaves together.

The way I approached my first portfolio project isn’t unique, it’s a fundamentally human thing to do—jump first, ask questions later. But these weren’t just beginner mistakes—they were symptoms of designing without a system.

Systems Thinking: The Missing Framework

For the purposes of this blog, I want to define what systems thinking means to me.

Let’s go back to my original approach—gluing leaves together. Even if I managed to solve a problem with the right leaf, it wouldn’t be scalable, and it wouldn’t be an actual product, but just a lonely leaf certain to wither and die.

With a systems thinking mindset, a designer can create a solution that naturally grows from the branch, or potentially blossoms into its own branch or drops the seed for an entirely new tree. In product design, we’re not just creating a single solution, but an ecosystem of interactions that provide users truly intuitive and seamless experiences. We want one feature to work with another feature, one layout to complement another.

Our dev teams, design teams, and product leaders need to be on the same page. This level of thinking is considered, deliberate, and prioritizes value to the entire product ecosystem. And this mindset scales, too. So that marketing teams can identify value propositions more easily, researchers can deliver more actionable feedback, and customer support can provide better help.

Try Again, Friend

Here’s what I should have done with Food Friendly: Started with the outcome. Instead of reimagining an entire POS system, I needed to design one leaf on an existing branch.

Here’s an example of the rewritten prompt:

Original prompt: “Design an app that streamlines the communication workflow for front of house restaurant employees and simplifies allergy checks, pre-shift meetings, and food inventory.”

Systems-thinking prompt: “Design an app for restaurant servers to check and communicate dish allergens while placing orders.”

The prompt works because it builds on existing architecture. Every POS system has order-taking functionality—that’s table stakes. Notice that I’m just adding ONE feature to an existing workflow—allergen checking during order-taking.

Now the scope is clear. The designer can iterate on the basic order flow, then layer in the allergen functionality. No need to reinvent the entire forest—just one useful leaf.

I’ve learned this lesson the hard way. Now I experience AI tools making the same mistake daily. Think about it: AI can generate those 24 design decisions I struggled with in seconds. Without systems-thinking—without knowing which leaf to grow first— that speed becomes chaos.

If this was just a story about my mistakes, it would be a footnote. But this pattern—velocity without vision—is about to define our entire industry.

| Approach | Without Systems Thinking | With Systems Thinking |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | ”Streamline all restaurant communications" | "Check allergens during ordering” |

| Users | Everyone (FOH, BOH, managers) | Servers only |

| Features | Multiple (allergies, inventory, schedules) | Single (allergen checking) |

| Complexity | 24+ design decisions | 3-5 design decisions |

| Timeline | Endless iteration | Ship in weeks |

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In the age of AI, product development has become remarkably easy. Claude builds applications in minutes. ChatGPT writes websites in seconds. Teams are “supercharged”—but here’s the problem: velocity without vision creates the same cascading complexity I faced, just faster.

The question becomes: Are we designing products, or just assembling parts?

We’re at a point where building is trivial and architecting is essential. The teams that will thrive aren’t the fastest builders—they’re the ones who know what’s worth building first.

The Gift of Getting It Wrong

I’m grateful I got Food Friendly wrong. It took years to understand my real mistake. It wasn’t the rough edges I was embarrassed about—it was trying to solve every problem instead of defining one worth solving.

Food Friendly taught me that in design—whether you’re using Figma or Claude—you can’t sprint your way to coherence. You have to design it in from the start, or you don’t get there at all.

The tools will keep getting faster. But the discipline of systems thinking? That’s the advantage that actually compounds.